“This is our world now… The world of the electron and the switch, the beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying for what could be dirt cheap if it wasn’t run by profiteering gluttons, and you call us criminals. We explore… And you call us criminals. We exist without skin color, without nationality, without religious bias… And you call us criminals. You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, you cheat, and lie to us and try to make us believe it’s for our own good, yet we’re the criminals.” – Lloyd Blankenship, The Conscience of a Hacker[1]

Within the multitudinous body of contemporary works dealing with the surveillance society, Mark Andrejevic’s 2007 book iSpy seemed to stand out the most. While it was not necessarily the most up-to-date work of the bunch, we (myself and Jesse) were interested by some of the ideas he presented on the capitalist side of the surveillance society. The book deals with the work of being watched, and how our voluntary participation in the surveillance state is also our voluntary donation of labor. Our goal with the overall project was to pare down some of Andrejevic’s ideas (namely his Marxist bent toward the way we’re employed by the surveillance society) and use them as a lens through which to view the increasingly complex private surveillance assemblages. This paper will be built around a Marxist critique of Facebook, which might be the least patriotic sentence I’ve ever written. I chose this direction after working through some of the major points of Marxist economics and realizing how truly exploitative and asymmetrical the relationship between Facebook and its users has become. Ultimately we seek to update iSpy and direct the focus toward Big Data and see how Andrejevic’s ideas apply in the new world of infinitely vast voluntary surveillance.

As requested, this paper isn’t going to be incredibly formal, and in some places might read like a checklist of our (okay, my) thought process as the idea of a Marxist critique of the surveillance system emerged. This isn’t breaking new ground, obviously; we’re heavily indebted to Andrejevic’s book and his thinking, we just wanted to go further into left field and see how his ideas fit the new model.

A Brief History of the Internet

The initial notion we began to work from was that privacy had become a form of currency. In cases like Facebook and Google, they often provide extensive services for free; Facebook is still the preeminent provider of social networking and has practically created its own market, while Google has (especially in the case of Yours Truly) muscled into Microsoft’s territory by providing online document editing comparable to Microsoft’s Office Suite, cloud storage, and its Gmail is one of the most popular email service worldwide, packing in almost 290 million users.[2] All of these services are regularly improved and updated, have near-as-makes-no-difference 100% uptime and, most importantly, cost no money. As someone who came of age with the Internet, I have seen the rise of the information economy and lived within it. To wax nostalgic, I do recall the time when there was no money in the Internet (except, of course, for adult entertainment – it’s the world’s second oldest profession); practically from the dawn of the World Wide Web, which is essentially the forward-facing aspect of the Internet as we understand it, free services like Geocities were available to create and host your own websites[3]. These were days when perhaps an entire site could fit on a floppy disk (the old 1.44 MB variety) and was hand-coded using knowledge that had been made freely available – if you knew where to look. The early 90’s saw an Internet that was, if only for a brief period, a realm free of capitalism and government intervention. As it became more and more accessible and people tied up their phone lines for hours on end (only to realize that the pace of connectivity had lagged behind that of interesting content generation), the Internet swiftly became monetized. While large companies like Microsoft and Yahoo offered email and other services for free, the Internet had come out of its Rousseau-like state of nature and become a place of commerce, initially to buy and sell goods that were not immediately available in the physical realm. Government and corporations moved quickly to create a more secure Internet to facilitate this process; it was a depressing moment when my friends and I realized that our hand-built payphone modems (that operated at a whopping 2600 Hz) would no longer function after the phone company upgraded to a digital network.

Speeds increased, storage became cheaper, and somewhere around 2005 the Internet reached a critical mass, and the notion of “Web 2.0” was born.[4] People associate that phrase with a variety of things, among them are the Web’s ability to support a true multimedia environment. Before 2004, services like YouTube were not available, and streaming videos was something the average user (see Lopez, Patrick J) could not envision. Early HTML and bandwidth restrictions limited the capability to rapidly upload and download complex data sets, so streaming videos or music (other than 8-bit or MIDI, which was the bane of many a late-night web surfer) were very limited commodities. In addition to greater quantities of storage and bandwidth, the mad rush to modernize the nation’s telecommunications law in the 1990’s[5]had the effect of heavily deregulating the market, helping to drop prices and increase access.[6] The time was right for a company with vision and capital to find a way to profit from this changing situation.

The Birth of Big Data

Enter Google, who by 1999 had entered the web search market with an algorithm that positively devastated the stale competition. Overnight they had driven AltaVista, WebCrawler and Lycos into obscurity. Beyond simply providing accurately weighted search results, Sergey Brin and Larry Page came up with a non-intrusive strategy to profit from their new search engine, and the Internet would truly never be the same. There is no general consensus on when “Big Data” was born, but as Google progressed and starting ranking pages in 2001 based on search results, I believe the game was properly afoot. Their PageRank[7] system provided a wealth of data to advertisers looking to piggyback on the popularity of certain searches and sites; their storehouse of data (provided by users at no cost to Google other than simply owning the equipment and paying the bills to keep it running) and advanced tracking algorithms allowed for targeted advertisements on a scale never before seen. Since the October, 2000 launch of AdWords, the customer-facing aspect has changed very little since Google has wisely kept their advertisements (and sponsored page results) unobtrusive.[8]

Google has gone on to create a variety of services, as mentioned earlier, that include a whole host of productivity apps, from word processing to spreadsheets to email. All of this is stored for you, accessible anywhere, always available – and every last shred of information from your web searches to your emails to your lousy budgeting spreadsheets exists somewhere on a Google-owned server. If you use Google Chrome, the web browser that, like its search engine forebear, lays waste to the competition, then every last bit of data produced by your use of Chrome is the property of one Google, Inc. Like every other company with skin in the Big Data game, Google has a Byzantine end user license agreement (EULA) that no one outside of privacy watchdog groups has time to read. As a user who has moved almost entirely to Google for his everyday tasks (like writing this essay), I simply trust that Google is keeping our interests in mind; they are after all the company whose motto is “Don’t be evil.”

Yes, Virginia, that is Surveillance

To the average person, the business of Big Data does not translate to surveillance; while it would be hard for them to define exactly what surveillance is (or better yet, to describe privacy), the imagery is pervasive. Closed-circuit cameras, wiretaps, the NSA, spy satellites and the Eye of Sauron all come to mind when asked what the nature of surveillance is. While all of these things are well and good, Andrejevic insists that we think beyond the visible assemblages of surveillance and assess the end goal. Haggerty and Ericson write that surveillance assemblages are, by their nature, robust and redundant – the eye of surveillance in the modern society is on us at all times, and that robust series of discrete sources creates a flow of information that terminates…where? In the day and age of cheap storage and bandwidth, data is profitable to store, and that goes as much for security complexes as it does for Big Data privateers like Google and Facebook. The terminus for these information flows is what Andrejevic terms the digital enclosure, the sum total of all data accumulated about a person’s activities, whereabouts, curiosities, photos, private conversations, financial information, buying habits, even how much you walk in a month can now be tracked (the latter was discovered, much to my chagrin, when looking at my Google Now information on my phone). All of this creates a data double, which Haggerty and Ericson claims to be a confluence created by “…abstracting human bodies from their territorial settings and separating them into a distinct series of discrete flows.”[9] These flows are then aggregated into a single entity that stands ready for multiple interpretation, or, in the case of Andrejevic via Karl Marx, to do work.

The Work of Being Watched

It would seem that if the surveillance assemblages are constantly in action, the very motions of our daily life seem to be producing vast reams of data. This data is an inert commodity, like iron ore, ready to be refined, shaped into whatever materials are needed for the industries reliant on Big Data. As we produce data within the information system (by our participation in the surveillance society), we provide corporations like Facebook the raw materials with which to build their products. And like any good capitalist industry, Facebook reinvest some of our raw material back into its own ecosystem to improve efficiency. The rest of it can be packaged and sold in an inconceivable number of ways. Meanwhile, the workers continue to toil away, generating new raw materials for the machine to grind up and spit out.

We are voluntary workers in this system, and our work does not cease at any point. Even while we sleep, the data we have created is a resource with unlimited potential use and can be put into motion at any time. Perhaps that wouldn’t some people’s definition of work, but fear not – there are now applications for your Android or iPhone that track you while you sleep. Programs like Sleepbot engage the accelerometer on your phone to determine when you move and shift in your sleep. Theoretically, the app learns your sleeping patterns in order to determine when your periods of lightest and heaviest sleep occur. You set a time before which you’d like to awaken, and voila – the app will awaken you when it determines you’re least likely to wake up groggy.[10]

Apps like Sleepbot represent a new generation of surveillant assemblages – passive data collectors that have the possibility of adding real world value to the user’s life. Haggerty and Ericson (and Andrejevic) are often hesitant to note the value-added benefits of participation in the surveillance society; many of the new generation of assemblages belong to the “Internet of things” and offer novel, sometimes life-changing benefits. One has only to scan the reviews of apps like Sleepbot on the Google Play Store to realize that, while it is most certainly a device that monitors your movements while you sleep (and it sounds downright terrifying in that context), it has worked wonders for people, especially college student types who need to make the best of the handful of hours of sleep they leave themselves after procrastinating on a major semester-long project.

This is the frightening beauty of the new generation of surveillance tools – we willingly participate in the system and work furiously to increase the size and scope of our digital enclosures. The corporate (and governmental) need for total information has found a perfect marriage with the life-enhancing wonders of the digital age. In the possibly apocryphal anecdote, Benjamin Franklin foresaw, with concern, a time when citizens of the world’s first constitutional democracy would give up too much liberty for their security. One wonders what he would have to say about our willingness to give up our privacy for a little convenience. When we began this project, Jesse and I talked in the language of privacy as currency, but ultimately our analogy was flawed; privacy is simply a commodity, an item to be traded, but ultimately not by us. Our data, despite the benefits we reap in the process of generating it, is not our own. The data double that follows is a monster that we can only barely control, and in Andrejevic’s view, we are nearly slaves to the process.

X Marx the Spot

If we want to start looking at things from a Marxist perspective – and who doesn’t? – then we’re on the right track. The Internet’s history has a feel of economic determinism to it, which makes sense given its genesis within the American capitalist system. The Internet did not develop freely, but has been shaped both in ways both subtle and overt by the institutions that were either threatened by it, stood to profit from it, or both. The language of Marx has existed in regards to the Internet since its very earliest days. I opened this paper with a quote from The Conscience of a Hacker, which served as an unofficial manifesto to the young Internet leftists, and it contains a number of criticisms aimed at the “profiteering gluttons” who control a system that could, if left unchecked, become the place some envisioned the Internet would evolve into: a place without names, racial identities, backgrounds – none of the markers that bind us to our caste or class in society. We would simply be bits of information, free to inhabit the nationless space of the Internet, a true paradise where the rules of capitalism would not apply. There are, of course, strains of this still in existence, but by and large the capitalist machine has snuffed out the dream of the digital commune.

The time has come to level the Marxist gaze at the surveillance society and its best capitalist friend, Big Data. The entire following section is taken from a variety of sources, but the University of Toronto’s Economics department has a great primer on the basic concepts of Marxist economics, and that was heavily utilized for creating the overall framework of this argument.[11]

At the center of it all is the worker, and true to Marx, the workers in the surveillance system have only their labor to sell. Our labor, though, is beyond what Marx could have imagined. We now labor in this system and produce by simply living our lives. As I touched on earlier, there is practically no point in anyone’s lives where they are not producing data. This data might just have potential uses (or criminally, none at all), but remains a potent product of everyday living. An alternate interpretation, and one more fitting to our work this semester might be that instead of labor, privacyis the one thing the worker can sell. In doing so, there is still the effect of producing information. As we are not truly sitting in factories shelling peanuts or creating iron widgets, our work is passive, and thus the labor is passive. Our exchange of privacy for goods (or wages) is, in fact, our method of labor. As the quantity of socially necessary labor requires some kind of tangible input from the worker, simply walking around all day and doing human being kinds of things does not constitute said input. We need something real, something at least vaguely quantifiable to input into the system in order to draw a wage and produce. Privacy has thus morphed from a value or basic human right into something less liberating, a method of exploitation. This is the very central notion of the work of being watched.

What then, is the commodity produced? While Marx requires no specifics (as this applies to all capitalist systems of production), we specify that we produce, simply, data. Data is possessed of myriad forms but is ultimately formless, and likened to the extraction of a raw material. We have no control over what shapes our data takes once it is extracted/created. Taking the raw material analogy further, we can define data as a material with unlimited potential uses. Iron ore can be treated in countless ways to create products, but iron ore has one fundamental weakness that data lacks: scarcity. Data is never scarce, and never will be so long as human beings do what they do and the technology increases in ubiquity.

How can we determine the labor value of our data? This is an easy question to answer in a general sense, but as Facebook and other Big Data producers are not forthcoming with their actual numbers, I couldn’t get as specific as I’d have liked in this. Frankly, it’s almost disgusting how little the value of our labor truly is. If we calculate the “congealed” labor cost of each quanta of data produced, one has to fold in the wages per worker with the costs of running the business. Estimates for building Facebook rarely exceed a million dollars, and the site itself can be viewed as the tool we use for production of data, but also as our wages. I will explore the how and why of the wage in the next section, but for now consider that Facebook has, according to their 2013 annual report, over 700 million people reporting to work every day, and their only payment is doing the work.[12] The infrastructure required to create this entity (the actual labor, data centers, bandwidth, building rental, etc.) is very expensive in terms of actual dollars – roughly $5 billion USD per year according to their 2013 annual report. That number presents the numerator in our equation, but the denominator – the actual quantity of data produced, is almost a semantic choice. Facebook claims it had 1.11 billion users as of March 2013 – for those keeping score at home, that’s 15% of the world’s population that were part of the data-generating business a year ago, and close to half of the 2.4 billion Internet users worldwide!

There are rumblings that perhaps Facebook’s popularity has peaked, but this is only one convenient example of the kind of coverage Big Data has. While 1.11 billion users is truly an impressive claim, it isn’t helpful in determining the kind of productive power that Facebook has. We can get closer to a value calculation by averaging the number of unique visits Facebook gets per year. 727 million multiplied by 365 days per year is a staggering 265 billion hits, per year. Each page hit, which generates data for Facebook, costs them a whopping 2 pennies. While the true generative capability of each user is truly an unknown, and since there is zero information on how Facebook aggregates and packages the data we generate, we can never know exactly what the true cost of “Big Data” is, but suffice it to say, Facebook is getting its two cents worth.

We can actually use some metrics to further determine how productive each user is. The beautiful website Kissmetrics determined (how else, by using the data we produced for them) that the average Facebook user creates 90 unique objects per month within the system.[13] The average user spends 700 minutes per month performing their self-determined socially necessary labor, a Marxist term that takes on an ironic flavor, given the apparent social necessity of using Facebook! We create one new object for every 8 minutes that we work on Facebook, and given the averages, that’s 99 billion new objects per month, or over a trillion objects created per year. Viewed that way, the cost per object created is down to $.004 USD per object. I just want to remind you that we do this voluntarily. What we cannot accurately quantify is the value of each object to Facebook; my posting status updates about the rabbit I saw on my lawn can only have so much worth in fiscal terms…probably. It wouldn’t take the world’s most complex algorithm to aggregate my status updates, identify certain nouns (I could write this in Python in an afternoon, and I’m a terrible programmer) and the frequency with which they are used, then sell that kind of data to advertisers and oh, wait, we’re talking about exactly the function of Google’s AdWords, a system that Facebook rejected for a homegrown version. Why did Facebook reject Google’s excellent, established system in favor of their own? Profit. Why let another company feast on their data when they could develop their own targeted tools? If I didn’t actively resist Facebook’s advertising machine, there would no doubt be rabbit-oriented ads waiting for me the next time I opened the site.

I want to return briefly to the concept of scarcity. In the physical realm, physical capital is in finite supply; raw materials become exhausted or more expensive to generate (as they say will eventually happen to oil), work stoppages occur, sunk costs exist in the form of wages, and so forth. In the generative system that is Big Data, none of this occurs. Data cannot be exhausted, and once sold, it does not disappear. Nowhere else in the world does such a commodity exist, and that has the remarkable effect of making each quanta of data infinitely valuable. The ultimate worth of any given unit of the commodity is determined only by the creativity of human beings, and that might be the only other inexhaustible resource on Planet Earth. Short of nuclear annihilation or an extremely pervasive worldwide Luddite movement, this train is not stopping any time soon.

The Marxist critique breaks down, at least by technical definitions, when we come to the ideas of surplus value. The traditional view requires a ratio of capital expenditure that, at least in theory, really doesn’t exist in the world of Big Data. Since participation in the surveillance society is nearly constant, entities like Facebook have practically no expenditure to show for the volume of production that its workers put forth. It’s insane – if we think purely in terms of the data production system, Facebook’s only capital expenditure is the maintenance of Facebook itself in order to provide workers with the tools they need to exchange privacy for the commodity of data, and that basically only comes from the pool of data itself! A small percentage of our labor power goes toward improving the tool – by filling out surveys, clicking in certain areas and not others, complaining on Facebook about new features or bugs, all of these things are still data collected by the machine to improve itself. Very elegantly, Facebook (and others in the social networking surveillance industry) has created a near-perfect system that requires the barest amount of external influence to propagate. The beauty of these new mechanisms of social surveillance lies in the ability to exploit the workers to continue making their work more and more efficient. This is Taylorism come home to roost, only now those who control production have refined the process so much that the workers regulate themselves, because participation in improving the tools also improves the perceived wage.

Within the sphere of Big Data, surplus value is nearly infinite. So little external investment or energy is required that the workers will continue to produce and improve the system on their own, meaning that the cost or inefficiency index of the system itself is so low, it’s practically negligible. If the advanced capital is nearly nothing, the expanded capital and value of the commodities produces a ratio that gives almost 100% profitability. We maintain that nowhere in the world can you find such a perfect system for exploiting surplus labor; if your system costs you nothing to have your workers produce, then the ratio of exploitation is infinitely high.

Because of the efficiency of the system, Big Data does not suffer from falling rates of profit. Certainly, there might be a drop in the overall value of the commodities produced due to the vagaries of the marketplace (and the fact that everyone is getting in on the game, producing reams of data, and no one is exactly sure what to do with it all), but if we examine Marx’s suggestions for stemming the traditional decline in profits, you’ll see the system has in place the safeguards needed to guarantee an excess of profit and production.

- Increase the intensity of the exploitation of labor: Until such a day arrives that we have our brain activity actively mined to produce computing power and electricity (i.e. The Matrix) it will be very difficult to top the current rate of exploitation. As the commodity of data is being produced constantly (and voluntarily), the quantity of socially necessary labor nears 100%, and our wages are the use of the tools themselves. We are always working to build our digital enclosure, thus we are constantly producing the commodity. Short of coercion or the aforementioned rise of the machines, I cannot envision a way in which we could be further exploited. That’s why I’m not in marketing.

- Find means of cheapening the cost of labor in order to depress the wage level: Once again, the Big Data gods have thought of everything. Literally the only way to depress the wage level further would be to open source Facebook or to make us starting paying them for it. Considering that music services like Spotify have a monthly fee that enables the listener to chew through hours upon hours of music (without advertisements, of course) means that you are paying someone to provide them with copious amounts of free market research on the latest listening trends. On top of that, services like Spotify (and many others) now have Facebook logins enabled, which means you’re paying Spotify to send your data to Facebook if you link the two together (which, for a while there, was mandatory.) Facebook and Spotify aren’t alone in getting in on the music game; a few years ago Google launched its own streaming music service, with a twist; you could now upload your collections to the cloud, voluntarily sharing your music tastes with Google. For the record, Patrick J Lopez has now listened to the Season 2 Battlestar Galactica soundtrack in its entirety over 150 times. That’s shameful to me, valuable to Google. Not long after Google Music launched, they too offered a pay radio service. Not even your listening habits are safe.

- Reduce the costs of the elements of constant capital by technological change and increasing the scale of production: This might as well be the byline for this whole project. Big Data is the perfect blend of surveillance technology, psychology, rapid technology growth and scale. When we talk of asymmetries of power, the breadth and scope of the gaze is indescribably vast compared to those who are being watched. The absolute ubiquity of surveillance technology and the dendritic nature of its integration into every aspect of American (and increasingly, world) culture means that technological change is already occurring at breakneck speeds. We have found the perfect fusion of consumer-driven and institutional demand; we want it faster, we want it cheaper, we want less hassles and less demands on our dwindling attention spans, and they are giving it to us. In return, we are giving them everything they require and more; the surveillance assemblages are truly gluttons, unable to sate themselves on the already vast amount of data being produced. The very byproducts of our society ensure that the already low capital costs will continue to crash as technology marches on.

- Expand and widen foreign trade: Sorry Marx, the internet is a truly global society (not counting North Korea and maybe Iran), so foreign trade is as wide as it can possibly be. There are, of course, ways of further breaking down barriers, but that requires acts of government, not corporations. Still, as it is in the interest for all parties in power to increase their surveillance utilization, perhaps the day is not far off when a globalized system of Internet regulations comes into being.

- Cheapen the cost of necessities: Marx intended this as a critique of supply chains, both internal and external. If laborers no longer need a high wage to sustain their livelihood, then profit margins can of course be increased. Internally, shoring up inefficiencies in production and finding cheaper sources of raw materials were methods for suppressing liabilities. In terms of Big Data, the system is nearly perfect, only with time and iterations of the tools can they increase efficiency, but given what was discussed in the previous bullet point, it is certain that operations like Facebook and Google will continue to streamline their production methods to ensure their “supply chain” is strong an uninterrupted.

It’s remarkable how efficient the system truly is, and it starts (and this section ends) with the question of wages – what is the motivation for the worker in this scenario? This is exploitation on a scale that should rightly make Marx rise from the dead and die all over again; the perfect capitalist system for capturing every last ounce of surplus labor from, in the case of Facebook, 15 percent of the world’s population. We receive no tangible benefit from our labor, but clearly we are motivated at ever-increasing levels to participate, and now we need to determine why.

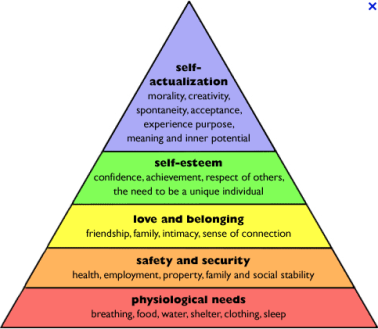

There is a staggering amount of material, most of it very recent, about the psychological drivers for the use of social networking. If you’re interested in an extremely thorough review of the study of Facebook, in 2008 MSU grad students Steinfield et al wrote a tremendous overview in the “Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology.” A large of body of research aimed at determining why people are so involved in Facebook (I might read this all again for my own mental health at some point), and it seemed to fall into a few different categories. Chiefly, people participate in social networking to maintain or increase social capital, either by maintaining existing relationships or adding to their stable of contacts via the passive forms of “friendship” that products like Facebook offer. The second point of examination, which in my book is a bit more sinister, involves the use of social networking (and the Internet in general) to promote self-worth and various other types of psychosocial development. There is direct evidence that links the amount of one’s social capital with behaviors that “…lead to better health, academic success, and emotional development.”[14] The accumulation of social capital requires cultivation and maintenance of relationships, and Facebook gives one the perfect tool for doing that. There have been mixed results in the research determining the psychosocial effects of heavy Internet usage, including indicators that strong “offline” ties can and have been replaced in many instances by weaker online ties, and this erosion of traditional human ties may have an overall negative effect.

Still, one has only to look around the Albion campus to see the scramble for social capital at work. While Facebook may be on the decline with the younger crowd, Twitter, Pinterest, Snap Chat and Instagram are going strong, all of which are tools used to see and be seen. While this essay has largely focused on the corporate aspects of surveillance vis-à-vis Big Data, the idea of “seeing and being seen” is the heart of these tools usefulness in the surveillance society. We have been empowered, as users, to surveil one another ad nauseum. The strong link between psychosocial well-being and social capital accumulation is really just a re-branding of the teenage (and, let’s face it, adult) need to be popular, to be well-known, and to be loved.

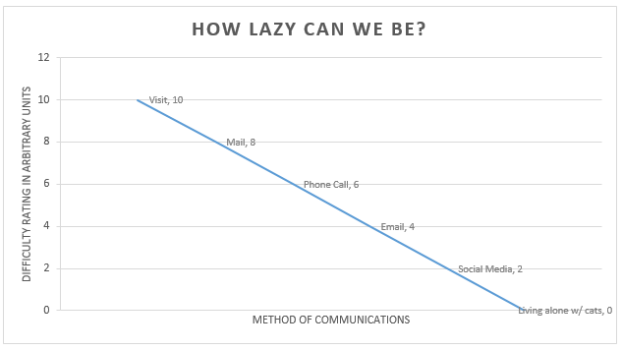

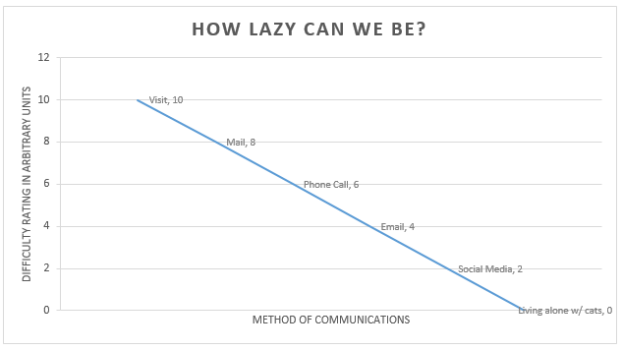

Facebook (and other tools) have given the average human being ways of creating and maintaining social capital far beyond what has ever been available in the past. When it debuted 10 years ago, Myspace was still the king of the hill, but its helter-skelter design and generally negative image kept it from being truly accessible. Before Myspace, email lists were the best way of keeping tabs on people, replacing the phone call as a way to communicate information instantly. Before phones, it was hand-written letters, and before letters people actually had to visit one another – perish the thought.

If you were to graph out the effort required to communicate with each of these methods, there would be a linear drop over time and technological development. Face to face is suboptimal – why bother when you can just Facebook message your friend?

Cheeky graphs aside, what has occurred with time and technology is a method of making friendship and relationships more convenient. This is not necessarily a bad thing! People keep in touch with family members via Skype and other video telephony products, and things like Facebook are great ways to share good news or just remind people that it’s your birthday. No one likes to feel forgotten or left out, and social media tools are a lot more convenient for reminding people of important events than by self-consciously pestering them. The ability to obtain and maintain social capital (and psychological health!) is perhaps the dominant reason for Facebook and social networking usage.

How does this translate into our wages for the work of being watched? Our most direct form of payment is the use of the tool – Facebook, Twitter, what have you. But the motivation for the tool’s use is to simply be part of society; Facebook in particular has created a market for this kind of social capitalization by appealing to our ever-shortening attention spans (and ever-increasing laziness) and harnessing our need for social capital. To that end, Facebook pays us in social capital; the surveillance state has now positioned itself to be a necessity for the most basic and fundamental human task: building relationships. The exploitative relationship between Big Data and its workers exists because the institutional desire for information has been matched with the personal desires of human contact.

Thus ends the basic Marxist examination of the economics of Big Data, which is merely a component of the surveillance society. The work of being watched is perhaps the most exploitative labor that has ever existed. The wage for our labor is simply the tool to interact with other human beings, to gain the necessary social capital to form and build relationships. The constitutive effect of participation in the surveillance society – with regards to Facebook – is that a kind of critical mass in your social circle can be quickly reached where, if you choose not to participate, you face a kind of passive ostracization. After all, if everyone in your social circle is enjoying the fruits of their labor (pun intended), it becomes more difficult to go back to old ways of communication. A perfect example is text messaging – today it almost seems like a novelty that our phones can call at all, when most communication is done in small bites via texting. The broad acceptance of tools like Facebook creates that critical mass where so many people are using it that they cannot afford to stop. A 2013 report by the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that, by and large, teenagers cannot stand Facebook; they cited “an increasing adult presence, high-pressure or otherwise negative social interactions (‘drama’), or feeling overwhelmed by others who share too much.”[15] The report also found that 94% of teenagers are using Facebook. If the majority of teenagers who make up the majority of teenagers are sick and tired of Facebook, why hasn’t it seen a large scale abandonment? Simply put, it’s because it has become socially necessary; if 94% of your peers are using it, you are immediately cut out of a massive amount of social capital if you decide to join the 6% who have already foregone Facebook. It’s clear then, that as much as the factory worker requires wages to survive, the Big Data worker requires the use of the tools of surveillance in order to attain their social capital and foment human relationships in this digital age.

In summary, we’ve basically concluded that participation in the Big Data aspect of the surveillance society is quickly becoming a social necessity. This leads to a practical enslavement by the corporations and entities that control the tools of social necessity – the Facebooks and Googles of today, and who knows what is coming down the pipe. We are always being watched because we submit to watching ourselves, to doing the work of building the digital enclosure, to empowering those that buy and sell these shadows of ourselves. This is the smartest and most exploitative system of labor ever devised, and we participate willingly.

[1] http://www.phrack.org/archives/issues/7/3.txt

[2] http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/06/whoa-its-2012-and-the-worlds-most-popular-email-service-is-hotmail/259054/

[3] http://content.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1936645,00.html

[4] http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

[5] http://transition.fcc.gov/telecom.html

[6] http://www.galbithink.org/bandwidth.htm

[7] http://www.sirgroane.net/google-page-rank/

[8] https://www.google.com/about/company/history/

[9] http://www.englweb.umd.edu/englfac/KChuh/Haggerty%20Kevin%20and%20Ericson%20Richard%20The%20SurveillantAssemblage.pdf

[10] http://phandroid.com/2013/09/07/sleepbot-helps-you-track-your-sleep-promising-a-better-morning/

[11] http://www.economics.utoronto.ca/wwwfiles/archives/munro5/MARXECON.htm

[12] https://materials.proxyvote.com/Approved/30303M/20140324/AR_200747/#/1/

[13] http://blog.kissmetrics.com/facebook-statistics/

[14] https://www.msu.edu/~nellison/Steinfield_Ellison_Lampe(2008).pdf

[15] http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/05/21/teens-social-media-and-privacy/